“Can democracy survive 2024?” was the title of a Financial Times big read published at the beginning of the year. Almost half of the world’s adult population will go to the polls this year, and democracy will be pushed to its brink. The world’s most populous country – India– will vote too, something the whole world should be closely examining.

Text: Ruhan Anjan Kartik

In a Western liberal democracy, we often view democracy as the foundation of a free and fair society, however, this is not the case all across the world. Democratic backsliding has been rampant over the past few years and youth are more tolerant of autocracy due to disillusionment with the status quo. In India, this disillusionment mainly stems from a perceived inability of youth to affect the political processes. Since politicians are not attempting to appeal to the youth, young people continue to view sociopolitical issues as insignificant compared to economic prosperity or are simply unable to contribute due to societally rooted issues of class or caste.

As the West looks for a path out of Chinese interdependence, there is a clear emphasis on the global south and especially India as a potential partner. India is a democratic country with a capitalist economy and thus a counterbalance to China both regionally and globally. Hence the West has often turned a blind eye to the increasing democratic backsliding such as restrictions on free press and crony capitalism, best depicted by the prime minister Narendra Modi’s close ties to Indian business and retail tycoons, that have plagued the country in recent years.

Furthermore, the West often views the world’s global order as hegemony or a bipolar setting. However, the rise of a “multipolar” or rules-based global order has been touted by the likes of Russia, China, and India in recent years. This is important, as India does not view itself as purely an ally of Western-based values, but as a superpower with its own view of global institutions and socioeconomic models, as it rightly should.

”India does not view itself as purely an ally of Western-based values, but as a superpower with its own view of global institutions and socioeconomic models.”

The context of the national parliamentary election

To truly understand the context of the upcoming election in April-May, we have to look at the character of India’s prime minister – Narendra Modi. Raising from an extremely humble background, he has shaped his image as a charismatic common man’s leader. Acts such as renaming his residence to Lok Kalyan Marg or “People’s Welfare Street” and abundant welfare schemes for farmers and rural populations which are marketed with his imagery reinforce this claim.

It is important to remember that Modi rose to power on a Hindu nationalist platform, and his party the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has its roots in the RSS, a Hindu nationalist paramilitary volunteer group. Divisive actions such as the Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019 which was criticized for being discriminatory toward India’s Muslim population, and the recent opening of a temple in January where a mosque was abolished previously are clear indications of a change from India’s nature as a secular democracy to a protector of Hinduism and the Hindu people.

”There are clear indications of a change from India’s nature as a secular democracy to a protector of Hinduism and the Hindu people.”

On the global stage, the floating idea of India renaming itself “Bharat” and Modi’s framing of India at the G20 summit, as “Vishwaguru” or “world’s teacher” raised eyebrows. This change in rhetoric is cause for concern, as it creates an ideal narrative for a Hindu-based religious-political system, and many fear it to be the beginning of a pivot toward an Israel-like state, where the existence of the state is rooted in defending a particular religion’s rights and voice rather than one of acceptance and multiculturalism.

From a Western perspective, it may be incomprehensible, but Modi is genuinely popular. During his ten years of power, economic growth has remained steady, and the Indian middle class has boomed. Transport infrastructure and the digitalization of the nation’s economy have also skyrocketed. However, wealth inequality and unemployment, especially among youth, have increased while women’s labour participation, investment in research and development, as well as foreign direct investment (FDI) have declined. At a sociopolitical level, inter-religious conflicts, violence, and crackdowns on various minorities have seen an increase.

This election comes at a critical time for the nation, as it aims to position itself as a non-aligned mediator and a partner in an increasingly complex and tangled geopolitical world. A key example of the crossroads the nation encounters is in its arms deals. Russia is India’s largest arms supplier due to historic ties, but France has contributed about 30% in this sector in recent years. This signals not just how the election’s outcome, but also how the global and especially the West’s response to the result could have strong repercussions for global economics and geopolitics. For example, a negative reaction from the West can trigger a bolstering of Indo-Russian relations, which the West cannot afford.

”The nation aims to position itself as a non-aligned mediator and a partner in an increasingly complex and tangled geopolitical world.”

The election process

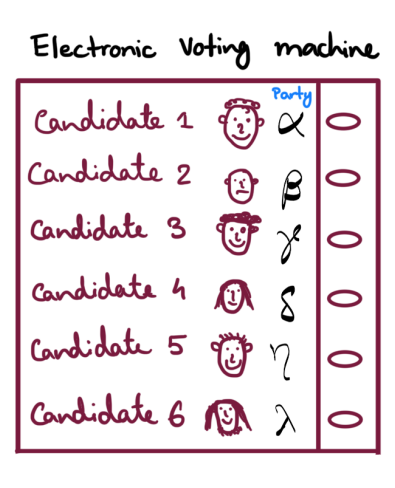

India has an independent electoral commission that oversees that the elections are free and fair. With polling stations in the middle of forests and deserts, this is an election like no other. It is organized over 5-6 weeks in phases such that every one of the over 900 million eligible has an opportunity to vote. These phases are organized such that during each phase there are 90-100 constituencies voting and the electoral commission is not spread too thin. With many lacking literacy and even official identity certificates, an ink mark is applied to demarcate those who have voted.

The 543 members of the lower chamber of the legislature, of which the prime minister is also a member, are elected directly by the citizens of India in a first-past-the-post system. As India has hundreds of parties, political alliances are often formed. The largest alliance is the national democratic alliance (NDA) of which the ruling BJP party is a member. The prime minister is the head of the legislature and has significant power in the executive, while the role of the president is mostly ceremonial. The Prime minister is in charge of national policies as well as representing the country on the international stage, hence holding immense power.

Outcomes and repercussions

India currently is facing a lack of opposition to Modi’s BJP. India’s main opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC) is essentially a family dynasty, having had three generations of prime ministers whose terms spanned over 35 years. However, their current lack of leadership and corruption compared to Modi’s popular support and his successful campaigns have reduced the opposition’s chances to almost null.

This means a third term for Modi is not just likely, but almost inevitable, with state elections over the past year reinforcing this forecast. Many fear a third term could help the current ruling party amend the nation’s constitution irreversibly to a Hindu republic, which would have repercussions in a region whose stability is already at a knife’s edge. It also aligns with a global rise in autocratic tendencies and could create further inter-religious conflict, especially between the Hindu majority and significant Muslim minority. It might make Western alliances increasingly challenging, as such a shift would likely be the boundary for what the West can ignore and accept in its search for a counterbalance for China. India is touted as the next economic powerhouse, and while this election may not change that, it might amend the nation’s path to economic and geopolitical take-off.

The author is a quantum technology student in Aalto University who is invested in his home country’s politics.